In 2021, the sixth assessment report of the IPCC led the UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres to describe the current climate change crisis as a “code red for humanity.”

At COP27, the recently concluded UN climate change conference, at Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, Antonio used even stronger words to describe the current situation:

“We are on the highway to climate hell, with our foot still on the accelerator.”

Antonio Guterres

UN Secretary-General

Source

Table of Contents

In 2022, the climate crisis continues to ravage countries around the globe with floods, droughts, heatwaves, cyclones, wildfires, coral bleaching events, and more. Simultaneously, global emissions have bounced back after the temporary slowdown during the pandemic.

It was hoped that COP27 would move the needle on climate finance and other levers to address the climate emergency. However, with COP27 now behind us, something else is needed to compensate for the slow pace of progress.

The Critical Role of the Finance Sector in Addressing the Climate Crisis

Capital markets have a critical role to play in enabling climate transition by ensuring the efficient flow of financing from investors to issuers wishing to address climate change risks.

To meet the 1.5-degree Celsius target of the Paris Agreement, every bank, insurer, and investor will need to adjust their business models, develop credible plans for the transition to a low-carbon, climate-resilient future, and then implement those plans. Furthermore, investments need to flow away from high-emissions activities such as expanding fossil fuel production capacities to climate financing – solutions for reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, removing emissions from the atmosphere, or increasing resiliency to the effects of climate change.

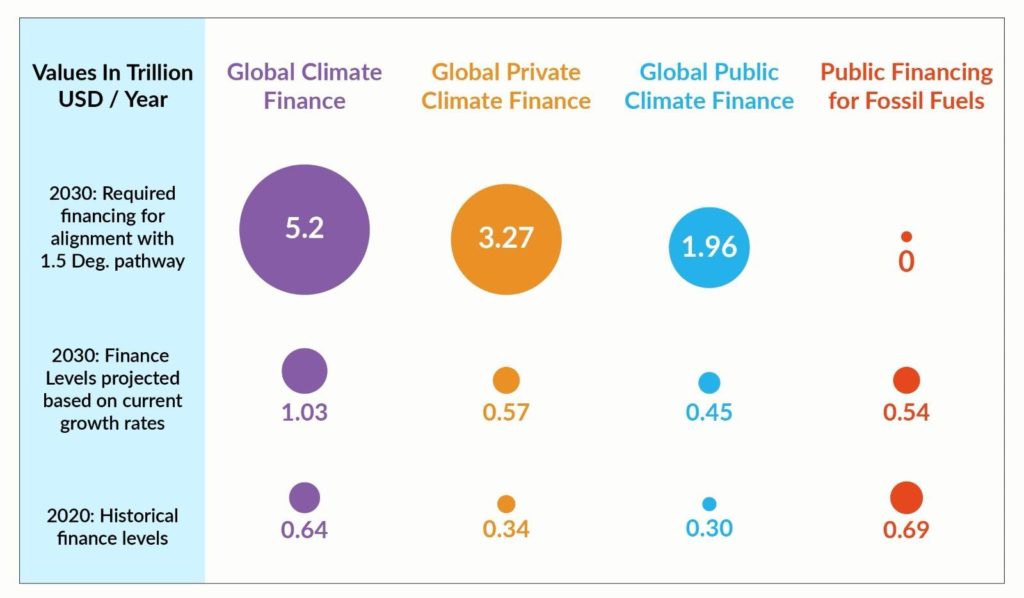

The Glaring Gap in Climate Finance

The finance sector is currently falling short of its role as a driver for climate action in the global economy. While climate finance is growing, the growth is nowhere near the pace – more than 10 times the historical growth rates – to meet the Paris goals. Moreover, many of the world’s leading financial institutions continue to invest in fossil fuels, commodities that drive deforestation, and other activities that may put the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C goals out of reach.

The State of Climate Action 2022 Report provides some revealing insights into the current progress of the finance sector, alongside several others concerning climate transition. While things are moving in the right direction, there is a need to accelerate the transition.

Sources: World Bank Carbon Pricing Dashboard, State of Climate Action Report 2022

Note: Average values for required private and public climate finance by 2030 are displayed for simplicity; actual estimates are in the range of ± 0.65 USD trillion. The sum of private and public finance does not exactly match global (total) climate finance due to the averaging and rounding of values.

Apart from increasing overall climate financing, there is also a need for balancing mitigation finance (funding activities that reduce emissions) with adaptation finance (funding resiliency measures). The latter has been significantly lagging.

Global finance for adaptation accounted for an estimated USD 46 billion in 2020, less than 8% of global climate finance. This is far below the scale that needs to help low-income countries protect lives and livelihoods from floods, storms, droughts, and sea-level rise.

While the Glasgow Climate Pact called for the doubling of adaptation pledges by 2025, this pledge was not reaffirmed at COP27. There is no mention of any quantified goal for adaptation finance in the COP27 cover text. There is a third category of climate finance, “loss and damage,” which received much attention at COP27. The Sharm-el-Sheikh Implementation Plan calls for establishing the financial and institutional structure for a global “loss and damage” fund to compensate developing countries for the adverse effects of climate change. While this has been touted as one of the few positive outcomes of COP27, many questions remain on how the fund will be financed and distributed.

Bridging the Great Finance Divide

Emerging economies, including those in South Asia, Southeast Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Latin America, have high infrastructure growth requirements in the coming decades as well as high vulnerability to climate change.

Therefore, investments in these regions towards climate change mitigation and adaptation are equally critical. However, close to three-quarters of global climate finance in 2020 was spent in the advanced economies, including North America, Europe and China, as reported by Climate Policy Initiative. Additionally, the vast majority of climate finance in emerging economies was sourced from domestic public financial institutions. Therefore, emerging economies have remained dependent predominantly on domestic public finance for climate solutions rather than cross-border public or private finance.

Unfortunately, the Covid-19 pandemic has led to the development of the “great finance divide,” as highlighted in the UN’s Financing for Sustainable Development Report 2022. During the pandemic, while developed countries gained access to ultra-low interest rates to fuel pandemic response and economic recovery, higher borrowing costs in developing countries led to a stalled economic recovery and, in some cases, unsustainable levels of debt.

As a result, developing and low-income countries have significantly reduced their ability to invest in climate change mitigation and adaptation, as well as other sustainable development goals. This has been further exacerbated by the effects of the conflict in Ukraine on rising inflation and associated challenges.

One of the solutions for tackling the great finance divide is global debt cancellation to free up fiscal space in developing countries and to compensate for the shortfalls in climate financing. Negotiations at COP27 brought up the concept of debt cancelations in the context of failures of developing countries to deliver on previous climate financing pledges. The final cover text only acknowledges concerns around the growing debt burden but does not go as far as mentioning debt cancellation as an option.

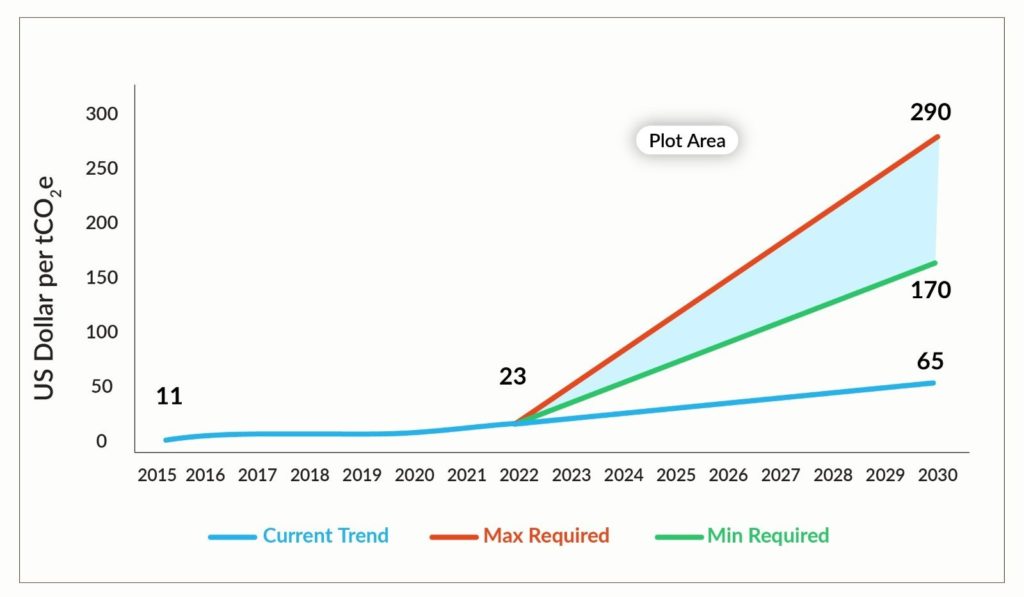

The Need for Higher Carbon Pricing

One of the enablers of investment flow towards economic activities that address the climate crisis is strong climate pricing regulatory regimes around the world.

As per the World Bank Carbon Pricing Dashboard, the current range of carbon pricing (carbon tax or price of emission allowances) varies from as low as 1 USD/tCO2e to 137 USD/tCO2e, with a median global value of 23 USD / tCO2e as of April 2022.

The final cover text of COP27, the Sharm-el-Sheikh Implementation Plan, acknowledges the gap in climate finance but does not lay out a clear roadmap for bridging it. However, the text calls for shareholders of multilateral development banks and international financial institutions to reform their practices and priorities to align with global requirements for scaling up financing to address the climate emergency

The median carbon price has increased by only 12 USD from 2015 – or less than 2 USD per year. Higher carbon prices within an aggressive timeframe across all geographies (less variation) would send the required signal to markets.

Sources: World Bank Carbon Pricing Dashboard, State of Climate Action Report 2022

The Need for Private Finance to Step Up

The private finance sector needs to demonstrate leadership by increasing its commitments toward climate transition and, more importantly, by translating commitments into action. This is particularly true in the context of limited progress achieved at COP27 on climate finance.

The current rate of progress in redirecting investments to climate solutions is insufficient. Some of the factors impeding climate finance are beyond the control of private financial institutions and arise from geo-political or policy environments. However, at a global level, the private sector is currently contributing more than the public sector to financing climate solutions. It can arguably drive change faster in all geographies, including emerging economies.

The Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ) commitment by ~450 financial institutions, representing over $130 trillion in assets, calls for aligning investment and lending with net-zero objectives. This demonstrates the potential of private sector leadership, but the committed institutions need to follow up with on-the-ground action.

To succeed in meeting their climate commitments, it is critical for financial institutions to integrate climate into everyday decision-making and investment strategies. There are multiple opportunities to consider in the form of financial instruments such as blended finance, green bonds, sustainable bonds, transition bonds, etc.

Finally, an increased level of engagement and collaboration with policymakers, corporate customers, climate tech companies, civil society organizations, and other stakeholders is necessary to accelerate climate transition.

Learn More on Fighting Climate Change with Data & AI

Data-Driven Sustainability: Achieve Business Value from ESG Data

After a successful webinar on digital transformation and sustainability, we organized a sequel titled “Data-Driven Sustainability Journeys from ESG Data…

A Fireside Chat With Chad Frischmann on Regenerative Solutions for Sustainability

In a recent fireside chat hosted by Gramener’s Sundeep Reddy Mallu, the CEO, and Co-founder of Regenerative Intel, Chad Frischmann…

Insights from Our Latest Webinar on Merging Digital Transformation with Sustainability Excellence

On Leap Day, 29th February, we had a successful webinar on Merging Digital Transformation with Sustainability Excellence. Vijay Rangarajan, Global…

The Global Biodiversity Crisis: Can Technology Help Achieve COP-15 Targets?

What is the Global Biodiversity Crisis? Biological diversity comprises the variety of living things on the planet. It includes the…

AI to the Rescue: 8 Animal Identifier Apps for Biodiversity Conservation

A small bird from the honeycreeper family, the Hawaiian po’ouli, was discovered in 1973. It went extinct in less than…

Here’s Why Financial Institutions Need Climate Transition Plans to Achieve Net Zero Goals

On 12th December 2015, 196 participants of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC) at the Conference of…